Mosses were among the first plants to evolve on land. This installation examines what can be learned today from their singular relationship with water (a beautiful primitive system implemented 450 million years ago by the small photosynthetic organisms and still going strong today).

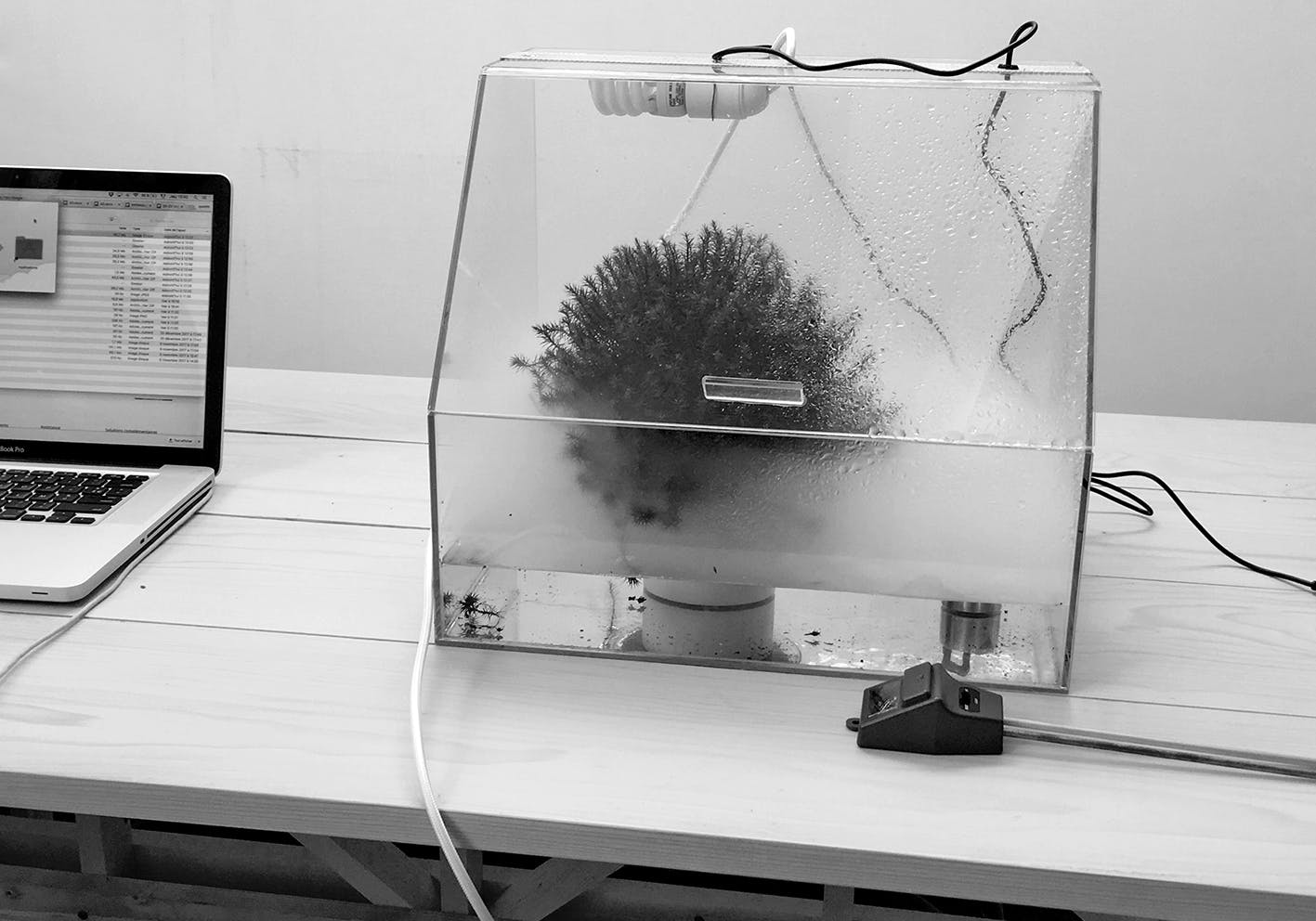

For the exhibition at XXXI, we placed a moss clump in a climate controlled glass case. We mist the moss in the case and then dry it out over a twenty minute cycle.

During this cycle, the moss clump perceptibly and with a certain vegetal enthusiasm, turns from lush green to apparent desiccation before returning to green once again.

This phenomenon is called « Anabiosis. »

Mosses were among the first plants to evolve on land. This installation examines what can be learned today from their singular relationship with water (a beautiful primitive system implemented 450 million years ago by the small photosynthetic organisms and still going strong today).

For the exhibition at XXXI, we placed a moss clump in a climate controlled glass case. We mist the moss in the case and then dry it out over a twenty minute cycle.

During this cycle, the moss clump perceptibly and with a certain vegetal enthusiasm, turns from lush green to apparent desiccation before returning to green once again.

This phenomenon is called « Anabiosis. »

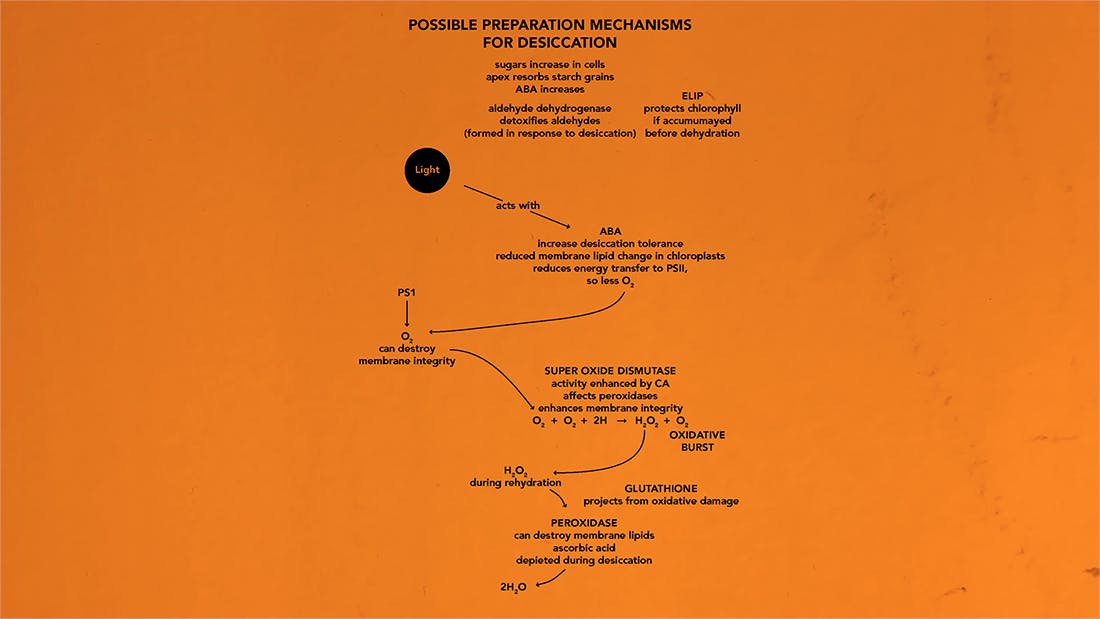

The clumps of moss displayed in Bryophytes were carefully foraged in our homeland. Carefully means that all the mosses we use are sampled in sufficiently small amounts not to threaten the development of their colonies. The video was shot in 4k with no timelapse at all. What you see is what happens. A spray of purified water turns crispy stems into soft, bouncy clouds of green. How can that possibly be?

It so happens that mosses can go from brittle and dusty to soft and lush in no time, due to their unique morphology: they do not require constant water.

Mosses relationship with water is one that takes a second to understand because it goes against most of what we take for granted as obligatory for life: that we need water. Mosses don’t have a complex vascular system like most plants and trees. The major downside to these vascular systems is the necessity of constant water. Dehydration is certain death. Once the cells collapse, there’s no going back. Mosses work surprisingly differently. They do use water to reproduce and grow. When fully hydrated, their water content is typically high, up to more than 1200% of their dry mass. But when water is absent, because mosses don’t have an internal water storage system like vascular plants do, they close and go into a kind of sleep.

This is anabiosis, a state of suspended animation. When in this state, limits of life and death as we commonly understand them are blurred. Some mosses can spend a very long time without being in contact with a single drop of water: days, weeks, years. Decades even. Instead of water, they stock up to 75 different kinds of proteins As moss comes into contact with water again, The proteins reconstruct cells and membranes that had become brittle and leaky during desiccation. With a single burst of water, they wake back up with extraordinary vigor and enthusiasm.